Digital contact tracing apps don’t make sense anymore

Updated: 2022-05-23

|

Warning

|

I am not a aerosol researcher, or virologist. I welcome thoughts and critique on this post. Contact me via Twitter or email. |

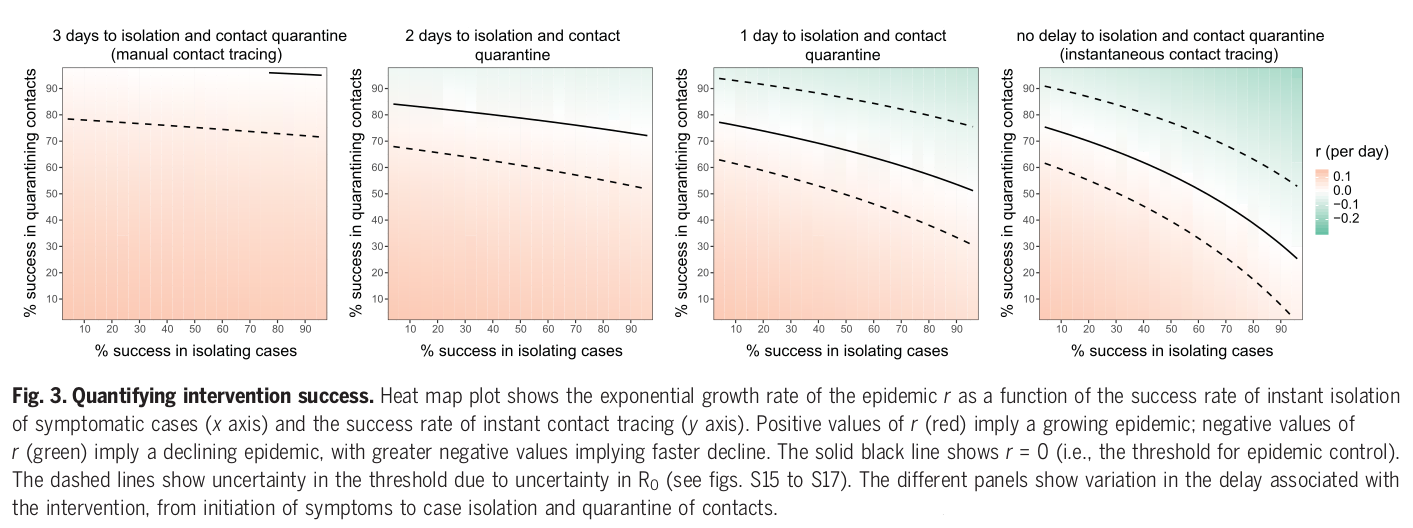

TL;DR: Proximity and time based exposure notifications made sense as a way to measure exposure risk when SARS-CoV-2 was thought to spread through respiratory droplets that quickly dropped to the ground. This meant if you were within two metres from an infected individual for less than 15 minutes, or you were farther than two metres from an infected individual you could assume almost no viral load was transferred to you, and thus no exposure risk. Thus, apps measured time and distance to determine exposure risk.

However, now we know SARS-CoV-2 is airborne and can linger in the air for minutes to hours and travel farther than two metres. This means other factors, such as the infected’s quality of mask and quality of air filtration, are key to determining how far the virus can travel and how long the virus can linger in the air, which then determines the viral load[1] that someone may have been exposed to, aka exposure risk. A digital contact tracing app has no way of knowing the contextual information about the environment someone is in, and thus does not have enough information to determine exposure risk. This means it no longer makes sense to rely on a digital contact tracing app.

The original paper

(Ferretti et al., 2020)[2] suggested the idea of digital contact tracing via a digital contact tracing app. These were the points made as to why a digital contact tracing app could be a tool to reduce infections during the COVID-19 pandemic:

-

manual contact tracing is too slow to bring down the R value, but a digital contact tracing app that instantaneously notified a exposed person to isolate would bring down the R value. Digital contact tracing apps have had success in China and South Korea.

-

"There is no delay between case confirmation and notification of contacts; thus, the delay for the contact quarantine process is the period from an individual experiencing symptoms to their contacts entering quarantine. The delay between symptom development and case confirmation will decrease with faster testing protocols, and indeed could become instant if presumptive diagnosis of COVID-19 based on symptoms were accepted in high-prevalence areas." (Ferretti et al., 2020)

-

"If testing capacity is limited, individuals who are identified by tracing may be presumed confirmed upon onset of symptoms, because the prior probability of them being positive is higher than for the index case, accelerating the algorithm further without compromising specificity." (Ferretti et al., 2020)

-

"With fast enough testing, even index cases diagnosed late in infection could be traced recursively to identify recently infected individuals, both before they develop symptoms and before they transmit." (Ferretti et al., 2020)

-

This could be done quickly with an algorithm, as opposed to manual contact tracing.

-

-

"Because time of infection is generally not known, the generation time is often approximated by the serial interval, which is defined as the time between the onset of symptoms of the source and the onset of symptoms of the recipient." (Ferretti et al., 2020)

-

"The app can serve as the central hub of access to all COVID-19 health services, information, and instructions, and as a mechanism to request food or medicine deliveries during self-isolation." (Ferretti et al., 2020)

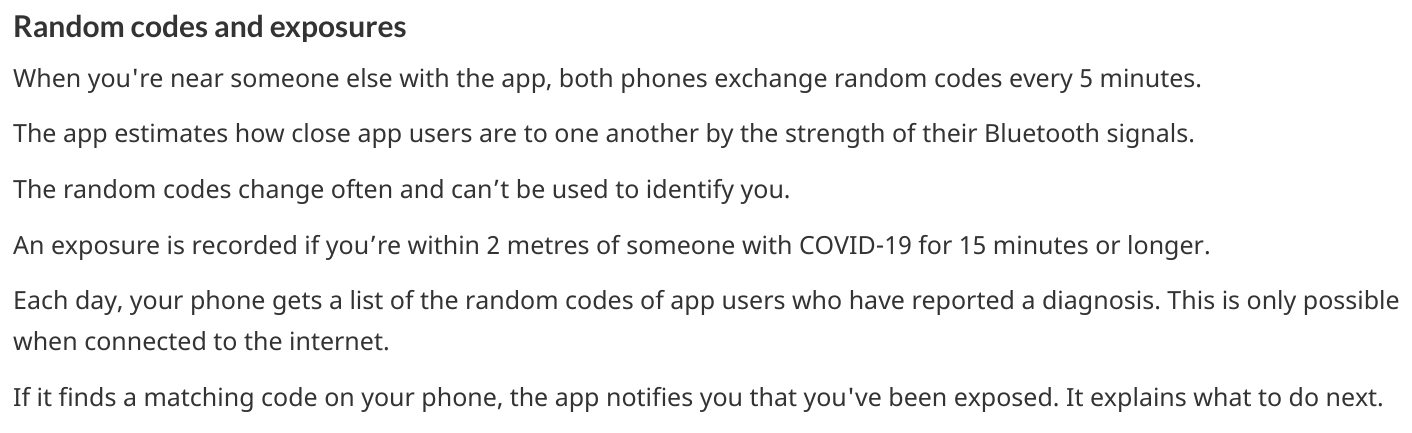

In fact, Canada has their own digital contact tracing app[3]. It works as shown below:

-

When you’re near someone else with the app, both phones exchange random codes every 5 minutes.

-

The app estimates how close app users are to one another by the strength of their Bluetooth signals.

-

The random codes change often and can’t be used to identify you.

-

An exposure is recorded if you’re within 2 metres of someone with COVID-19 for 15 minutes or longer.

-

Each day, your phone gets a list of the random codes of app users who have reported a diagnosis. This is only possible when connected to the internet.

-

If it finds a matching code on your phone, the app notifies you that you’ve been exposed. It explains what to do next.

The general idea around digital contact tracing apps is that based on some proximity and time threshold, in Canada’s COVID-19 app this is 2 metres and 15 minutes, you will be alerted with a notification that you were exposed to someone with COVID-19. Upon this notification, you would quarantine to prevent infecting other people. It’s been a year since the release of Canada’s digital tracking app, and I took a peek at the report.

Maybe you’re wondering why I’m so interested in this. Well, digital contact tracing sounded like a super cool idea of an application of technology in public health. I was excited about the app and downloaded it myself. Unfortunately, I’ve deleted it, and in my review of the report maybe you’ll see why.

My review of the "Interim report on social and economic determinants of app adoption, retention and use"

The Canadian government came out with a report[4] reviewing the impact Canada’s digital tracking app on the pandemic. My thoughts are in in italic. When I say "council" I am referring to the "COVID-19 Exposure Notification App Advisory Council".

COVID Alert has been downloaded over 6 million times, and 20,000 people have since entered a one-time key (OTK) following a positive COVID-19 test result, notifying other users that they may have been exposed to the virus.

As of Feb 2022, there have been 6,893,423 downloads and 57,704 keys used. With a population of around 38 million, this means only 15-20% of the population has downloaded the app. There are apparently 3.64M tracked COVID-19 cases (all time) in Canada when I checked on Apr 18. This means the app had access to around 1.6% of positive cases to determine if someone could have been exposed, and then alert them. Such a low number of reported cases means this app is a inaccurate tool for someone to use as a judgement to whether they have been exposed or not. I found all these values via a quick Google search.

COVID Alert is a national exposure notification app that will alert users if they have been in close contact with other users who have tested positive for COVID-19.

Getting only reports for "close contact" gives the impression that you can only get sick from being "close" to someone. This is incorrect, since researchers have discovered cases in which no one was a close contact with each other, yet still people were becoming infected. You can get sick without being near someone who is sick.

Although individuals experiencing these barriers are unable to use the app directly, they can still benefit from it if other people use it. For example, if someone with the app receives a notification, they may decide not to visit a medically vulnerable person. This action protects the vulnerable person from potential exposure, even if the vulnerable person does not have their own compatible phone.

Much of the app is based on voluntary action. The phrase "may decide" is used, and this makes it seem as if vulnerable people are at the mercy of those who have the latest technology and can use the digital contact tracing app. We can’t assume people will act with the best intentions, and certainly cannot just leave vulnerable folks at the hands of able-bodied and privileged people. The report also implies that it’s okay to exclude vulnerable individuals from this tool. Everyone deserves access to tools to protect themselves.

Currently, British Columbia, Alberta, Nunavut and the Yukon have not adopted the COVID Alert app.

If nearly all of Western Canada isn’t able to use the app, then that’s a huge piece of data missing.

The report outlines reasons that users uninstall the app:

-

Perceives that the app is not user-friendly;

-

Believes that the app will not be substantially effective without broader public uptake;

-

I believe this as well, and this statement is why I uninstalled the app. Digital contact tracing can provide some insight if most of the population uses it, much like in China, South Korea or Taiwan. With less than 5% of positive cases entering a key and only 18% of the population having downloaded the app (not sure how many actually use it), the data is just random noise.

-

-

Does not receive any exposure notifications and therefore assumes that the app is not performing as designed;

-

Obviously this is because there’s literally such low numbers of data being collected, which gives people the impression that COVID-19 isn’t transmitting around that much, which is totally incorrect. The app simply can’t reflect the true transmission rates because not enough data is being entered.

-

-

Lacks understanding or is confused by on how the app works (e.g., contact-based and not location-based);

-

Experiences anxiety related to receiving a notification and possible consequences (e.g., isolating, testing); or

-

if you were to receive a diagnosis, you would probably prefer a human tell you, rather than an app. With an app, there’s no one to help you answer follow up questions or to calm you down. This is why we need humans.

-

-

Experiences technical issues such as battery life on some phone models.

-

Bluetooth is incredibly battery draining.

-

Here are some new features they’ve added:

-

narrowing the exposure notification window to periods when a COVID-positive user was the most infectious, by allowing the user to voluntarily enter their symptom onset or test date;

-

this is horrible. There are cases when people who are asymptomatic are infectious. Additionally, with all the COVID-19 variants, someone becomes infectious at different rates. We can’t simplify down COVID-19 to just when we think someone is most infectious. This also seems very hard to determine, because of how variants aren’t turning up as positive on rapid tests and the lack of tests in the first place.

-

-

allowing users, specifically for health care workers, to manually turn the app off when wearing the appropriate personal protective equipment in areas with high likelihood of being near COVID-positive persons (e.g. test centres, long-term care facilities); and

-

this makes some sense, but the feature could be abused and up to each person to judge if they think they are wearing appropriate personal protective equipment.

-

-

allowing users to clear the exposed state following a negative test result, in order to permit users to receive new exposure notifications.

-

guidance must be given on this. Since rapid tests aren’t always accurate, someone may take a false negative as being no longer infected, when in fact they are still contagious.

-

These points oversimplify COVID-19 to simply "avoiding" someone when they are most infectious, and encouraging people to prematurely return back to society when they may still be infectious. Transmission can occur when you’re not even beside an infected individual. The virus can linger in the air. Nothing related to the "air", such as letting users know about CO2 levels or air transmission is mentioned.

Under "Strategies to reduce barriers and increase adoption, retention and proper use of the app":

Establish a baseline number of app downloads that would be considered sufficient to appropriately measure the effectiveness of the app in reducing the spread of the virus;

The council acknowledges that WHO said in 2020 that "no established methods for assessing the effectiveness of digital proximity tracking" but then goes on to say that "The Scientific Director of the Big Data Institute at the University of Oxford recently indicated that apps such as COVID Alert are having a positive impact, even in the absence of specific quantifying metrics and that the concept of a minimal adoption rate is less relevant to these apps because this type of tool is effective regardless of its level of up-take". I’m not sure if I believe this.

The Government of Canada has begun to broadly consider how the COVID Alert app could potentially extend beyond a government service to Canadians and the public health system towards a tool that will also support Canadians and businesses in our economic, social and mental health recovery and restoration. To this end, it will be critical for individuals and businesses in Canada to have trust in the app’s ability to support their safe return to worksites and universities, their reopening of businesses, and their use of modes of transportation including public transit (air, marine, and rail services) until the pandemic is declared over. The advice of the Council will help to inform the Government’s next steps in all of these regards.

The statement above directly contradicts with the statement that the Canadian government will work on "eventual wind-down of the app, including recommendations for the timely destruction of data." There is also the idea that people think an app will "magically" make things easier for faster.

Position COVID Alert as one additional tool at the disposal of Canadians, to better situate its position within the broader public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic and to highlight success stories that would resonate with Canadians; […] This will be critical in achieving wider uptake, which will involve clear communications, ongoing engagement with diverse partners and communities; and continuous improvements to the app (e.g. new functionalities and emerging technologies that could help to re-open parts of the economy)

This frustrates me. We have methods that work and do reduce cases,such as high quality masks, air filtration and increasing outdoor air supply. I’m disappointed that none of these were mentioned. We don’t need more apps. Instead, we need to use methods that work.

Through the deployment of the COVID Alert app, the Government of Canada has committed to deploying a technology-based solution that will assist Canada in flattening the curve and limiting the spread of COVID-19.

The public has to trust health experts and actively prevent infection by getting booster shots, masking up, getting routinely tested for COVID-19, and self-isolating until no longer infectious. Government needs to track data, such as waste water and CO2 levels, so we can prepare for the future. We shouldn’t be investing so much time and energy into a tool we aren’t even sure works when we now understand that COVID-19 is airborne.

Technology based solutions frequently simplify complex solutions into simple models that may not be accurate. It’s been two years since the pandemic began, and we have more knowledge of the virus. There are tools that do work, such as CO2 monitors, which can help someone decide if eating at a restaurant is safe or not. Digital contact tracing, at its current state, does not provide any useful information to citizens. There are no metrics mentioned, after more than one year of use, if this app prevented anyone from being infected. We can’t say the app has assisted at all in limiting spread of COVID-19 if there’s no metrics to back that up.

The report fails to mention anything about COVID-19 being airborne and what the app plans to change to take into account that distances more than 2 metres may still expose someone to COVID-19.

With more variants emerging, the government has a responsibility to update its citizens about these variants and provide data to help citizens make informed decisions.

Our world is constantly changing, and software must adapt to these changes, not the other way around. However, it seems today that the world is constantly catering to the software, simplifying down complex situations only to have the world slap us in the face later.

There are two issues that stand out to me:

-

the digital contact tracing app was designed with the idea that COVID-19 transited via respiratory droplets

-

more people need to download and use the app to make the app a useful and reliable tool

However, now that we know COVID-19 transmits through aerosols and that the accuracy of the app depends on the numbers of people using it, here are the questions I want to raise on why I think there’s a low chance of Canada being able to adopt a digital contact tracing app and why I think the digital contact tracing app is inaccurate:

-

Is proximity the best measure?

-

What about testing and variants?

-

Adoption of the app by the public?

Is proximity the best measure?

The paper I mentioned above also stated that:

By devoting considerable resources, including police investigation, 75 of the 92 cases of local transmission were traced back to their presumed exposure, either to a known case or to a location linked to spread (15). Linking cases via a location generally includes the possibility of environmentally mediated transmission. Therefore, the large fraction of traceable transmission in Singapore does not contradict the large fraction without symptomatic exposure in Wuhan.

It’s understandable that Western nations assumed COVID-19 wasn’t airborne, as other deadly illnesses like cholera and polio spread through fluids and fecal matter. Declaring a virus is airborne is also alarming, and as a global body, WHO may have thought it was their responsibility not to accidentally set a false alarm. However, we now know that COVID-19 is airborne[5].

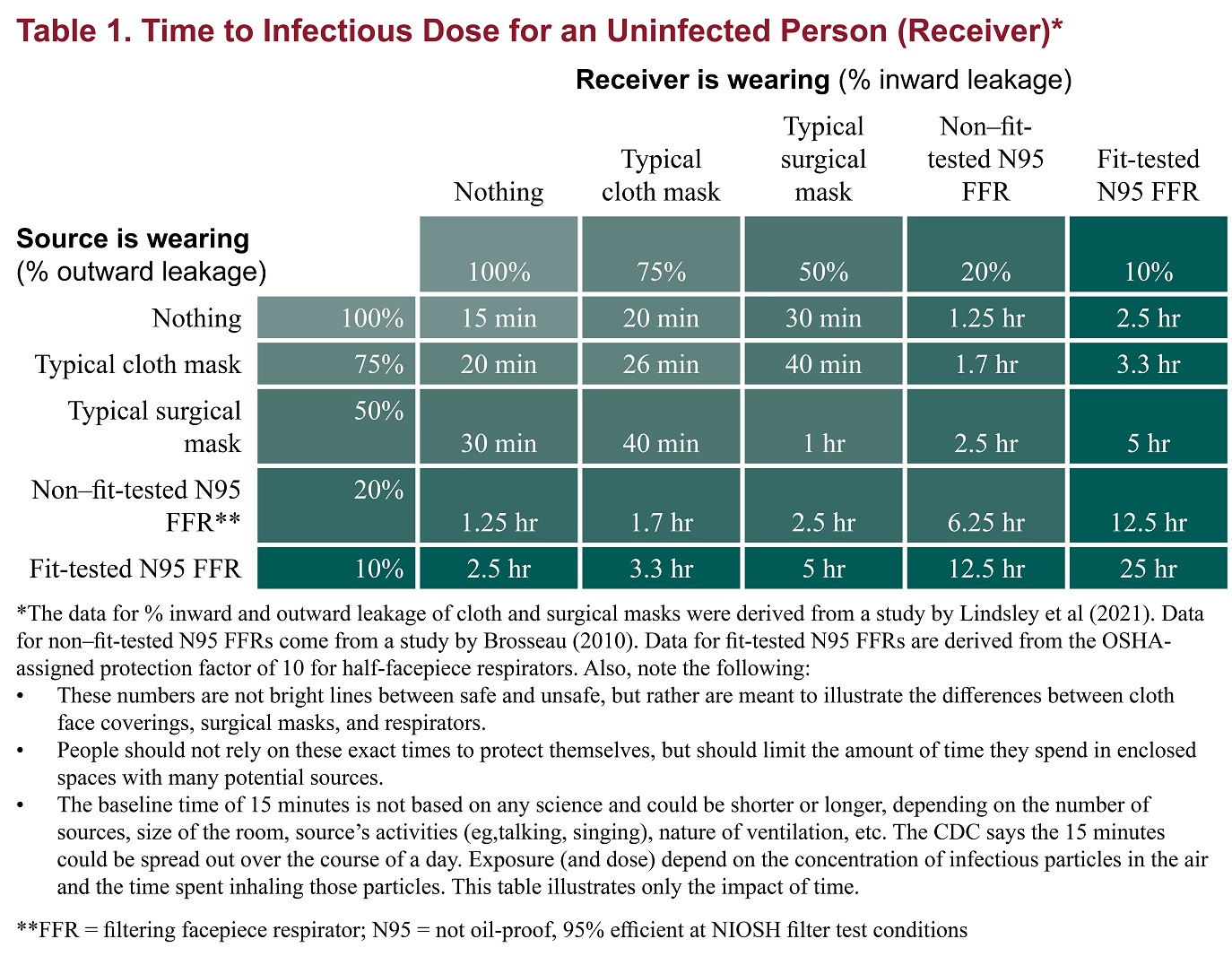

Digital contract tracing apps which use proximity to determine exposure reduce COVID-19 transmission into the notion that we only need to be near sick people to get sick. When not much was known about COVID-19 transmission and it was believed to transmit through respiratory droplets that quickly fell to the ground, this would have been a model that made sense. But with more research highlighting evidence on COVID-19 transmission occurring when people aren’t near each other and that particles of up to 100 microns can stay in the air, proximity isn’t a reliable measure for exposure and downplays how transmissible COVID-19 is. Canada’s digital contact tracing app uses 2 metres as a proximity measure, but you can be infected from distances much farther[6] and many factors (like masking and air filtration) play into what distance is "safe".

A one-size-fits-all 2-metre social distancing rule is not consistent with the underlying science of exhalations and indoor air. Such rules are based on an over-simplistic picture of viral transfer, which assume a clear dichotomy between large droplets and small airborne droplets emitted in isolation without accounting for the exhaled air. The reality involves a continuum of droplet sizes and an important role of the exhaled air that carries them. Smaller airborne droplets laden with SARS-CoV-2 may spread up to 8 metres concentrated in exhaled air from infected individuals, even without background ventilation or airflow. Whilst there is limited direct evidence that live SARS-CoV-2 is significantly spread via this route, there is no direct evidence that it is not spread this way.

With surface spreading viruses or fluid (liquid) spreading viruses, we don’t need to be near someone to get sick. People can get infected with cholera by using water from a stream that could be miles away from the infected person. We need to be in contact with that surface or fluid to get sick. In fact, there are several cases of COVID-19 transmission between people who have never seen each other, but have breathed the same air via air conditioning[7].

We get sick by interacting with the virus via contaminated air, not just by being near an infected person.

In virology lecture we are taught that airborne particles can be respiratory droplets or aerosolised particles. Respiratory droplets eventually fall to the ground, while aerosolised particles can linger in the air.

At the beginning of the pandemic, WHO made the erroneous judgement that COVID-19 was spread through respiratory droplets that eventually fell onto surfaces and then infect those that touch those surfaces. This mistake led Western nations to slap a sanitizer machine at every building entrance, increase their sanitization of desks and more surface focused cleaning[8]. On the contrary, many Asian countries have ignored the CDC[9], acting on research that paints COVID-19 as a much more infectious virus than WHO and Western nations think. And it seems to have paid off.

Why did WHO decide that COVID-19 wasn’t airborne? Well, since transmission was thought to occur through sneezes, coughs, etc, that expel large respiratory droplets, WHO thought that these respiratory droplets would just fall to the ground. Lots of medical experts were making the assumption that most viruses weren’t airborne since particles were bigger than 5 microns[10]. However, maybe respiratory droplets do stay in the air longer than we thought.

There’s a history[10] that may have been a reason why WHO acted the way they did.

In 1934, Wells and his wife, Mildred Weeks Wells, a physician, analyzed air samples and plotted a curve showing how the opposing forces of gravity and evaporation acted on respiratory particles. The couple’s calculations made it possible to predict the time it would take a particle of a given size to travel from someone’s mouth to the ground. According to them, particles bigger than 100 microns sank within seconds. Smaller particles stayed in the air. Randall paused at the curve they’d drawn. To her, it seemed to foreshadow the idea of a droplet-aerosol dichotomy, but one that should have pivoted around 100 microns, not 5.

The 60-Year-Old Scientific Screwup That Helped Covid Kill

So what happened? Why haven’t we been using the 100 micron metric? Well,

Part of medical rhetoric is understanding why certain ideas take hold and others don’t. So as spring turned to summer, Randall started to investigate how Wells’ contemporaries perceived him. That’s how she found the writings of Alexander Langmuir, the influential chief epidemiologist of the newly established CDC. Like his peers, Langmuir had been brought up in the Gospel of Personal Cleanliness, an obsession that made handwashing the bedrock of US public health policy. He seemed to view Wells’ ideas about airborne transmission as retrograde, seeing in them a slide back toward an ancient, irrational terror of bad air—the "miasma theory" that had prevailed for centuries. Langmuir dismissed them as little more than "interesting theoretical points."

The 60-Year-Old Scientific Screwup That Helped Covid Kill

And then after Langmuir disparaged Well’s work he came up with this:

In the report, Langmuir cited a few studies from the 1940s looking at the health hazards of working in mines and factories, which showed the mucus of the nose and throat to be exceptionally good at filtering out particles bigger than 5 microns. The smaller ones, however, could slip deep into the lungs and cause irreversible damage. If someone wanted to turn a rare and nasty pathogen into a potent agent of mass infection, Langmuir wrote, the thing to do would be to formulate it into a liquid that could be aerosolized into particles smaller than 5 microns, small enough to bypass the body’s main defenses. Curious indeed. Randall made a note.

The 60-Year-Old Scientific Screwup That Helped Covid Kill

Langmuir did eventually shift his tone and accept that airborne infection was possible. After Well’s died, Langmuir delivered a speech stating "problematic particles—the ones they had to worry about—were smaller than 5 micronsall[10]." And that screw up started it . However, particles that are up to 100 microns are also airborne!

While most viruses are 0.1 to 0.5 microns, viruses hitch a ride on the droplets that we produce when breathing, sneezing or coughing. From this experiment[11] there are droplets that measure at below or around 100 microns. This means someone’s sneeze can travel around a room.

Okay, that was a lot of reading. I wanted to set up why the virus being airborne is important and how digital contact tracing misses on this. Digital contact tracing apps seems like a fun algorithmic problem to determine who’s been near whom! Which is just another complex public health and social problem reduced into a algorithm. It seemed perfect.

But the app is missing a lot of context. For one, depending on whether or not the air is actively being filtered, being 6 ft (or 2 metres) may be enough distance, or it might not be. And depending on one’s mask, this further complicates what distance and time you can inhale infected air is "safe" from being exposed to infection, The app simply doesn’t know, and giving erroneous information is worse than no information. The app doesn’t know anything about the quality of the air. Distance doesn’t matter so much if the air is being constantly filtered. A CO2 monitor would be more helpful than an app that tells me if I’ve been near a sick person. Basically, the app totally simplifies and neglects how air transmission works. The only way you can tell if you’ve been exposed is if you have a CO2 monitor telling you if the air is being recirculated and whether it is being filtered enough such that you aren’t breathing in the air other people exhale.

Since COVID-19 virus is airborne, one should assume no distance and time near infected air is safe, unless they had data to tell them otherwise. For instance, it would be useful to know if I was in a restaurant or building that had bad air quality. Much of the public has no access to knowledge of whether their air is being filtered or not, or the quality of the filter. If we aren’t able to access high quality, real time data on positive cases, understanding our air quality is the next best piece of data we can use to make informed choices.

As Ali Alkhatib[12] says in his blog post "We Need to Talk About Digital Contact Tracing"":

Digital contact tracing systems that render the world as normally distributed space with spheres of influence and contact characterized by radio waves will consistently leave us with dangerously wrong pictures of our exposure.

We Need to Talk About Digital Contact Tracing

I’ve mostly been discussing science, but please check out his blog post to learn how digital contact tracing excludes the most vulnerable, gathers unrepresentative data, how proximal tracing doesn’t maintain privacy and how proximity is a dangerously simple way to model and think about COVID-19 transmission.

To get infected, viruses require affinity and avidity with the human receptor.

There’s a lot of chemistry, physics and biology involved in getting infected. First, the physics of viruses. Viruses spread through surface, liquid and air. The physics for each medium is different, and it’s important we all have some basic understanding of how to prevent transmission given the medium of spread.

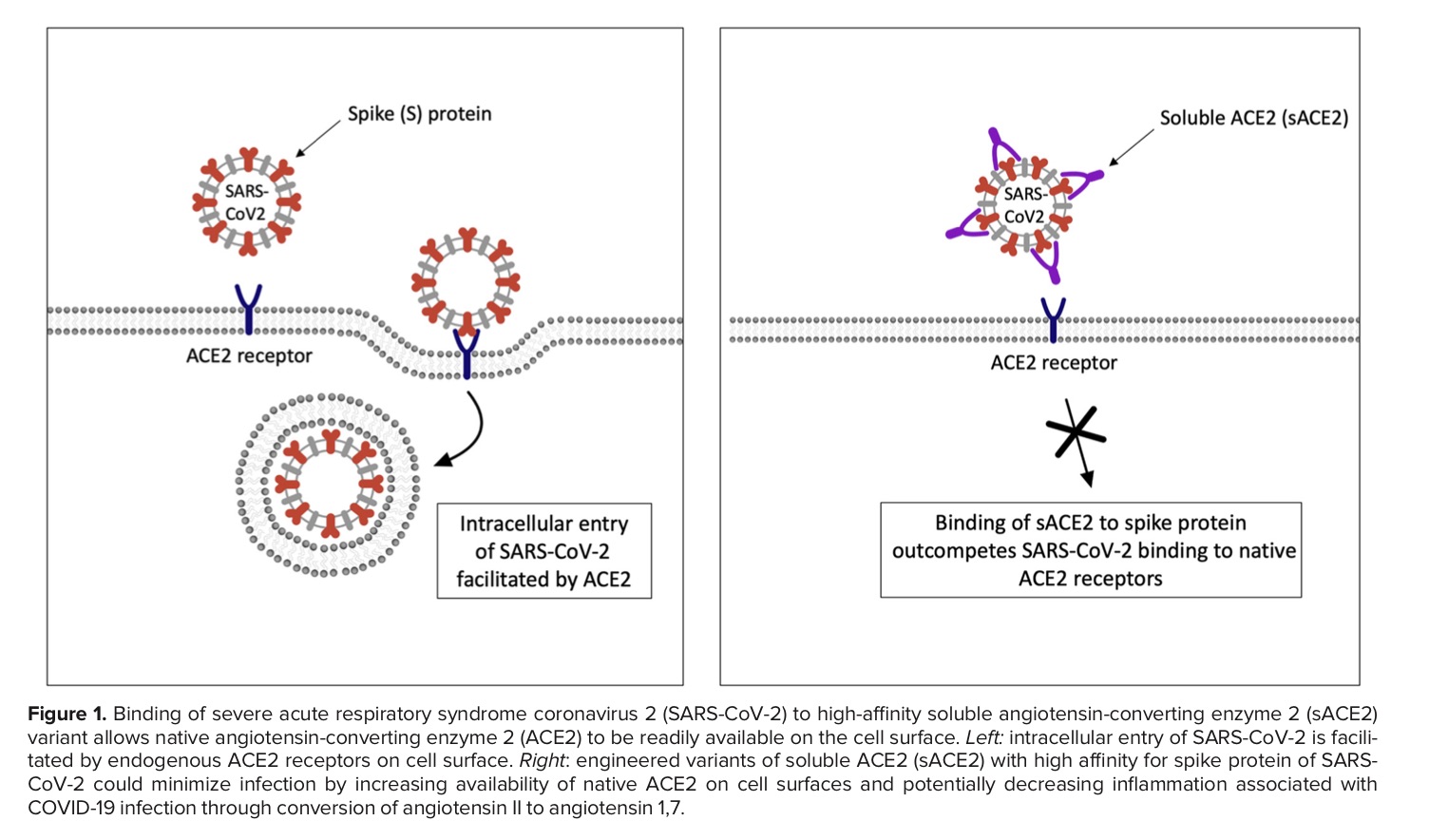

To become infected, viruses require affinity and avidity. What does this mean? Well it’s time for chemistry. Affinity is how strongly two molecules will react with each other. We can think of this as the binding event between the virus and human receptor. The stronger the binding event, the better. More specifically if the virus has more affinity to bind than the native molecule that usually binds to the human receptor, then the virus is on its first step to infecting us. Next, we must have avidity, which is the accumulated strength of multiple affinities[13]. Affinity isn’t always enough, thus, if there’s more virus than native molecule, the higher concentration of virus can out compete the native molecule. Once some threshold is met, you are infected.

Figure is from this paper[14].

And the biology is how our body responds. Our immune tries it’s best to prevent the virus from damaging our body, but COVID-19 can cause "collateral tissue damage and systemic failure"[15].

Okay, so what does this mean? There are some things we can’t control, like how a virus spreads or which human receptor the virus will bind to and how strongly that virus will bind. But there are some things we can control, like avidity (how many virus particles) and our immune response. We can control our avidity to a virus by wearing high quality masks and requesting better air filtration or choosing to increase access to outdoor air. We can control our immune response by getting vaccines.

Unfortunately, education on proper masks has been non-existent, with some health leaders suggesting that cloth masks are still okay to wear (they aren’t[16]).

Contact tracing apps make it easy to forget the physics, chemistry and biology of viruses. These apps boil viruses down to exposure time and proximity to infected individuals. Many important factors like the method of spread, avidity and immune response are pushed to the sidelines with software solutions, with millions of dollars going into these apps.

Testing and Variants

Testing

The Canada digital tracking app requires a one time key to use if you have a confirmed positive case of COVID-19. I would assume this means those who don’t have access to tests wouldn’t be able to self report their positive case or if they were feeling symptoms (I’m not sure).

This goes against the advice that the paper gives:

"If testing capacity is limited, individuals who are identified by tracing may be presumed confirmed upon onset of symptoms, because the prior probability of them being positive is higher than for the index case, accelerating the algorithm further without compromising specificity.""

Much of the success of the app relies on quickly and accurately detecting positive cases with testing. However, with variants that aren’t always showing up on rapid tests, the delay of results with PCR tests, lack of accessibility and economic barriers to testing, this severely limits who can get tested.

Until we have faster, more accurate, more accessible and cheaper tests, the accuracy of digital tracking apps will be pretty low.

As of now, there seems to be no way to report a self test.think about this deprecation with the current state of testing availability/eligibility. and you can still download the app? tell me i’m missing something someone please https://t.co/ueA49gUtVJ

— Bianca Wylie (@biancawylie) April 15, 2022

is there a way to report our cases to ontario gov? I cannot find anything anywhere to report to so cases of my family will be counted. https://t.co/bLSiImovma

— Amanjeev 𒄇 (@amanjeev) April 15, 2022

The main goal of the digital tracking app is to notify and allow someone to self-isolate before they even begin showing symptoms or infecting others. Without access to tests, this makes it very hard to achieve this notion of instantaneous contact tracing. Days matter a lot when trying to prevent the spreading of COVID-19.

Viruses mutate at random. A lot.

But viruses don’t mutate everywhere at random. We’ve observed with COVID-19 variants and other coronaviruses that there are some conserved regions that undergo mutation a lot less. For instance, the residues of the substrate-binding pocket are highly conserved[17] and don’t really undergo much mutation, since this protein is essential to replication and proteolytic processing.

But the spike protein on the other hand goes through a lot of mutation. For instance, many Omicron’s mutations[18] are associated with the ACE2 receptor binding and antibody binding sites (our vaccines currently target these proteins).

Mutations are random, but the random mutations that survive current drugs and vaccines are the mutations that will continue to spread. Mutations that occur on proteins like the main protease may also occur, but some mutations are more deadly to the virus than others, and these mutated viruses simply cease to replicate, ending their ability to spread.

With that being said, for current drugs and vaccines to continue working, we have to slow down the chance for the virus mutate. The likelihood of mutation increases as more and more people become infected. This means we must prevent infection.

People will argue that infection is mild, but getting infected isn’t just about getting infected. It’s about whether you become the new reservoir to the next COVID-19 variant.

Digital contact tracing apps can give someone an over simplified model of how COVID-19 transmits; using proximity doesn’t make much sense since the virus can stick around in the air and viral load is dependent on a lot of factors like masking and air filtration. The longer and more we get infected, the more variants there will be. It’s time to ditch the app and go back to tracking data and using methods like masking and air filtration; methods that work.

Adoption of the app by the public

I was excited by the announcement of Canada’s digital tracking app after hearing about the success in South Korea and China. However, as I highlighted above, I later uninstalled app because no one was using it.

The paper[2] mentions some important points. Firstly, in China the app was a success because:

Public health policy was implemented using an app that was not compulsory but was required to move between quarters and into public spaces and public transport.

Obviously, that sort of adoption has not happened in Canada and probably will not. Only 15-20% of the Canada’s population has installed the app. If we play with some simulations here and assume 20% of Canadians will self-isolate, maybe assuming 20% of infections will be stopped, this is still not enough to move COVID-19 into endemic phase. This analysis[19] done quite early during the pandemic, which was based on early research and the less transmissible original COVID-19 variant, states we only need to stop 60% of infections.

Other points the paper mentions, such as:

Successful and appropriate use of the app relies on it commanding well-founded public trust and confidence.

Is unlikely to occur in a Western society where people are more independent and less trusting of their governments.

Also claims such as:

The intention is not to impose the technology as a permanent change to society, but we believe that under these pandemic circumstances it is necessary and justified to protect public health.

…

It is noteworthy that the algorithmic approach we propose avoids the need for coercive surveillance, because the system can have very large impacts and achieve sustained epidemic suppression even with partial uptake.

are discussed in Ali Alkhatib’s[12] blog post. All in all, I see a low chance for the app gaining a large enough adoption for the app to become an accurate tool to use as a means to decreasing infections.

Conclusion

For a digital contact tracing app to have some impact on reducing infections we need:

-

access to lots of quick and accurate tests

-

a preventative mindset towards being exposed, as outlined in the paper: "If testing capacity is limited, individuals who are identified by tracing may be presumed confirmed upon onset of symptoms, because the prior probability of them being positive is higher than for the index case."

-

ability for people to upload self confirmed tests to the app

-

adoption of the app by 60%[20] of the population

-

people to actually self-isolate until they are no longer sick

-

a better way to measure exposure risk: using masking and air filtration to predict exposure risk or understanding that the virus can linger in the air, so letting users know if they have been in the same location as someone who was infected, regardless of how far or how long they were near that infected individual

However, to prevent new variants and prevent long COVID I believe we must work towards no infections at all, not just reducing infections. I understand this is a more extreme stance, but drug and vaccine development simply will always lag behind the virus, and developing drugs and vaccines isn’t easy! Since 100% (or even 50%) adoption and use of the app isn’t feasible, I don’t think digital contact tracing works in a Western society.

It’s not worth the time and money to keep trying to use digital contact tracing apps at this stage. Alberta spent $4.3 million[21] on their digital contact tracing app, which only notified 1,500 people of possible exposure.

Vaccines protect you from severe disease.

— Joey Fox, P. Eng, M.A.Sc (@joeyfox85) May 23, 2022

Rapid tests reduce your exposure to infected and highly infectious people.

Wear a respirator indoors.

Spend more time outdoors.

Besides that, DO EVERYTHING!

21/21https://t.co/RbUJoE4BmI

We know what works. Such as good quality masks, air filtration and UV learning (in the air, not surfaces) to limit viral load or inactivate the virus. We also have have the ability to measure metrics that can help us predict areas of increasing infection (waste water tracking) and possible exposure risk (carbon dioxide monitoring). In a Western society, the digital contact tracing app will not get us out of the pandemic.

With ideation help from 🦔