Update: 2022-05-28

|

Note

|

I talk about research and ideas in this blog post from a natural sciences/mathematical point of view. I’m not a researcher, so take my ideas with a grain of salt. I’m also trying to figure out for myself "What is Computer Science", so my ideas may be half-formed or contradictory. |

The natural sciences, like physics, chemistry and biology, are based on experiments which require vocational skills. But data curation and collection is meaningless without the theory to understand the data. If you want to develop vaccines or drugs, you need to study chemistry and biology. If you want to find the next smallest particle (quark anyone?) or far away planet, you need to study physics.

If you want to do research, think beyond the scope of what is known, and discover something new, then you need the theory, which means pursuing a theoretical degree (or learning the theory yourself). A scientist needs to think of ideas that don’t even exist. I believe theory allows you to come up with ideas that are correct and novel; you can’t come up with correct and novel ideas with just vocational skills. Thus, a scientist has to be both correct and novel to be successful[1].

Research has uncertain goals and uncertain rewards, which can scare people, including the people who decide to pursue research. Some people don’t care about being correct and novel, they might just care about being correct. I would say being correct vs. correct and novel is the difference between a chemical engineer and a chemist:

The old joke is that with chemistry you learn how to make a new molecule, but with ChemE you learn how to make 800 tons of it as cheaply as possible[2].

Of course, I’m not saying engineers can’t have novel and correct ideas, but you can be successful as an engineer just by being correct. If you’re a scientist who can’t think of novel ideas, it’s hard to be successful.

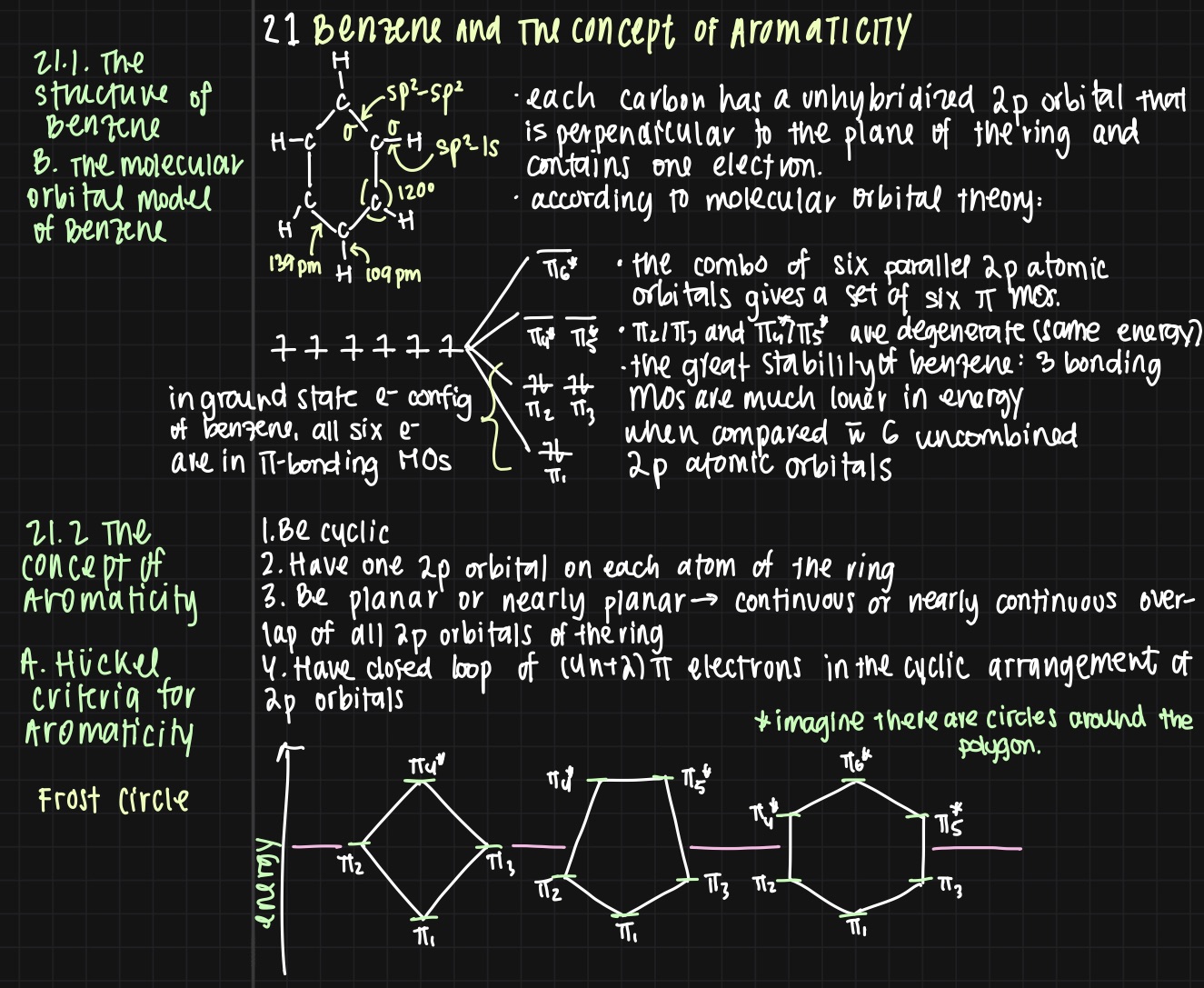

Thus, people may enjoy a certain field, but have no interest in advancing the field and that’s totally okay. Some people just take the elements on the periodic table for granted; they don’t care to know how electrons are "arranged" for molecules. However, the benzene’s arrangement of electrons is something I want to learn more about. On the other hand, I think genetics is cool, but I have no interest in understanding why certain alleles are closer to each other on a gene.

In the case that people just want to be correct, they may choose to do engineering. In terms of engineering, there are a lot of engineering disciplines to choose from, like chemical engineering, electrical engineering, computer engineering, environmental engineering, materials engineering, civil engineering, petroleum engineering, and many more. Compared to a degree in sciences like chemistry or biology, engineering degrees are more applied, and more focussed on correctness rather than preparing to discover new ideas. A chemist could probably work as a materials engineer, but someone with a degree in materials engineering would be more efficient and cheaper to employ. A materials engineer will study chemistry and physics, including topics like atomic bonding, electrochemistry, free energy, etc[3]. But a chemistry major and materials engineering major will study atomic bonds differently. For instance, a materials engineer will learn that ceramics include metallic and van der waals bonds[4] , and that would be the extent of a material engineer’s course material on atomic bonding. A chemistry major would learn about why certain bonds exist between molecules in the first place in a series of courses like "Electronic Structure of Atoms and Molecules"[5] and "Introduction to Quantum Mechanics and Spectroscopy"[6]. Engineers learn about processes to be efficient, correct and useful to industry by producing goods.

The natural science degrees (chemistry, physics, biology, math) have their place and the engineering degrees have their place. But what is the computer science degree? I’ve noticed that computer science is taught differently at universities, with the differences being quite significant. At some universities, the computer science major is part of the sciences, while at other universities computer science is part of engineering. Some schools tend to teach more theory, while others are more applied. This has led me to the question, Should the computer science degree prepare students to conceive novel and correct ideas or prep them with the processes they need in a technology industry?. Well, let’s look at the computer science curriculum of some universities.

The Computer Science Degree: An impromptu and informal analysis

|

Important

|

These thoughts are based on my experiences at UBC and any course information I could find online. I was able to easily find many course websites (which included a detailed syllabus, assignments, slides and labs) from USC and NU. I couldn’t find many course websites for UofT. Thus, take these thoughts with a grain of salt. |

UBC, USC, UofT and NU all offer the computer science degree as a bachelor in science. However,

-

at UBC (University of British Columbia), computer science is under the Faculty of Science

-

at USC (University of Southern California), computer science is under the Viterbi School of Engineering

-

at UofT (University of Toronto), computer science is under the Faculty of Arts and Science (for the St. George Campus at least)

-

at NU (Northeastern University), computer science is under the Khoury College of Computer Sciences

Comparison of Core Computer Science Courses Required for the Degree

I try to match the UBC version to other schools’ version.

| UBC | USC | UofT | NU |

|---|---|---|---|

CPSC 110: Computation, Programs, and Programming |

CSCI 102L: Fundamentals of Computation |

CSC108H1: Introduction to Computer Programming |

CS 2500: Fundamentals of Computer Science 1 |

CPSC 121: Models of Computation |

CSCI 170: Discrete Methods in Computer Science |

CSC165H1: Mathematical Expression and Reasoning for Computer Science |

CS 1800: Discrete Structures |

NA |

CSCI 103L: Introduction to Programming |

CSC148H1: Introduction to Computer Science |

CS 2510: Fundamentals of Computer Science 2 |

CPSC 210: Software Construction |

CSCI 201L: Principles of Software Development |

CSC207H1: Software Design |

CS 3500: Object-Oriented Design |

CPSC 221: Basic Algorithms and Data Structures |

CSCI 104L: Data Structures and Object Oriented Design |

CSC236H1: Introduction to the Theory of Computation/CSC263H1: Data Structures and Analysis |

NA |

CPSC 320: Intermediate Algorithm Design and Analysis |

CSCI 270: Introduction to Algorithms and Theory of Computing |

CSC373H1: Algorithm Design, Analysis & Complexity |

CS 3000: Algorithms and Data/CS 3800: Theory of Computation |

CPSC 213: Introduction to Computer Systems |

CSCI 356: Introduction to Computer Systems |

CSC258H1: Computer Organization |

NA |

CPSC 310: Introduction to Software Engineering |

CSCI 310: Software Engineering |

Co-op or 1 out of the project/inquiry based courses |

CS 4500: Software Development |

CPSC 313: Computer Hardware and Operating Systems |

CSCI 350: Introduction to Operating Systems |

CSC209H1: Software Tools and Systems Programming/CSC369H1: Operating Systems |

CS 3650: Computer Systems |

NA |

CSCI 360: Introduction to Artificial Intelligence |

NA |

CS 2810: Mathematics of Data Models |

NA |

CSCI 353: Introduction to Internetworking |

NA |

CY 4740: Network Security |

NA |

NA |

NA |

CY 2550: Foundations of Cybersecurity |

Overall Observations

After I compared computer science course offerings[7],[8],[9],[10] and the computer science core curriculum from each university, here are some things that jump out to me:

UBC[11]:

-

introductory computer science course taught in functional paradigm

-

there is a large focus on functional programming which is regarded as more "theoretical" due to its mathematical nature

-

the result of a larger focus on functional programming means students engage more with concepts like recursion

-

-

students are introduced to pointers and memory management in the second year, later than other universities

-

students must learn a lot more programming languages including BSL (dialect of Racket), Java, C, C++, etc.

-

UBC has recently released a industry focussed course called "Applied Industry Practices"", though it’s only offered in the summer

-

thus UBC does not have as many industry/skills type of courses as other universities

-

-

compilers course is based on functional paradigm (Racket)[12]

UofT[13]:

-

uses Python as first programming language

-

no need for students to take explicit software engineering course if they have done co-op. They can also choose out of a list of courses (meaning they don’t need to do a software engineering course)

-

courses tend to use Python and C for systems courses, and Java for OOP course

-

as a result of programming language choices, courses are more OOP and imperative based

-

has more industry type of courses like "Programming on the Web", "Natural Language Computing", "High-Performance Scientific Computing"

-

students are introduced to OOP first and imperative programming first (no recursion, pointers or memory management like UBC and USC)

-

compilers course is based on imperative paradigm (Using Python?)[14]

USC[15]:

-

uses C++ as first programming language

-

courses seem more continuous, with 103L following right off from the end of 102L.

-

probably because C is used, and C fits nicely with the operating systems course, data structures, and algorithms course

-

only other language used is Java for OOP

-

-

required to take ENGR 102, the engineering first-year students academy

-

required to take Introductions to AI and Internetworking

-

choice of choosing a capstone course of either "Design and Construction of Large Software Systems" or "Creating Your High-Tech Startup"

-

required to take an embedded systems course

-

has many "skills" focussed courses like "Professional C++", "Native Console Multiplayer Game Development", "Programming Graphical User Interfaces"

-

also has more industry type of courses like "Creating Your High-Tech Startup"

-

students are introduced to pointers and memory management in their first year, while they are introduced to recursion/functional programming in their second/third year

Northeastern[10]

-

first year computer science course is similar to UBC’s

-

two fundamentals courses (2500 and 2510), whereas UBC only has one (CPSC 110), before the OOP course

-

students are required to do a security course

-

there are both theoretical and proof based courses like computer-aided reasoning, verification, synthesis. I haven’t seen other universities have these type of courses at the undergrad level

-

there are also more industry and skills focussed courses like mobile development and web development.

-

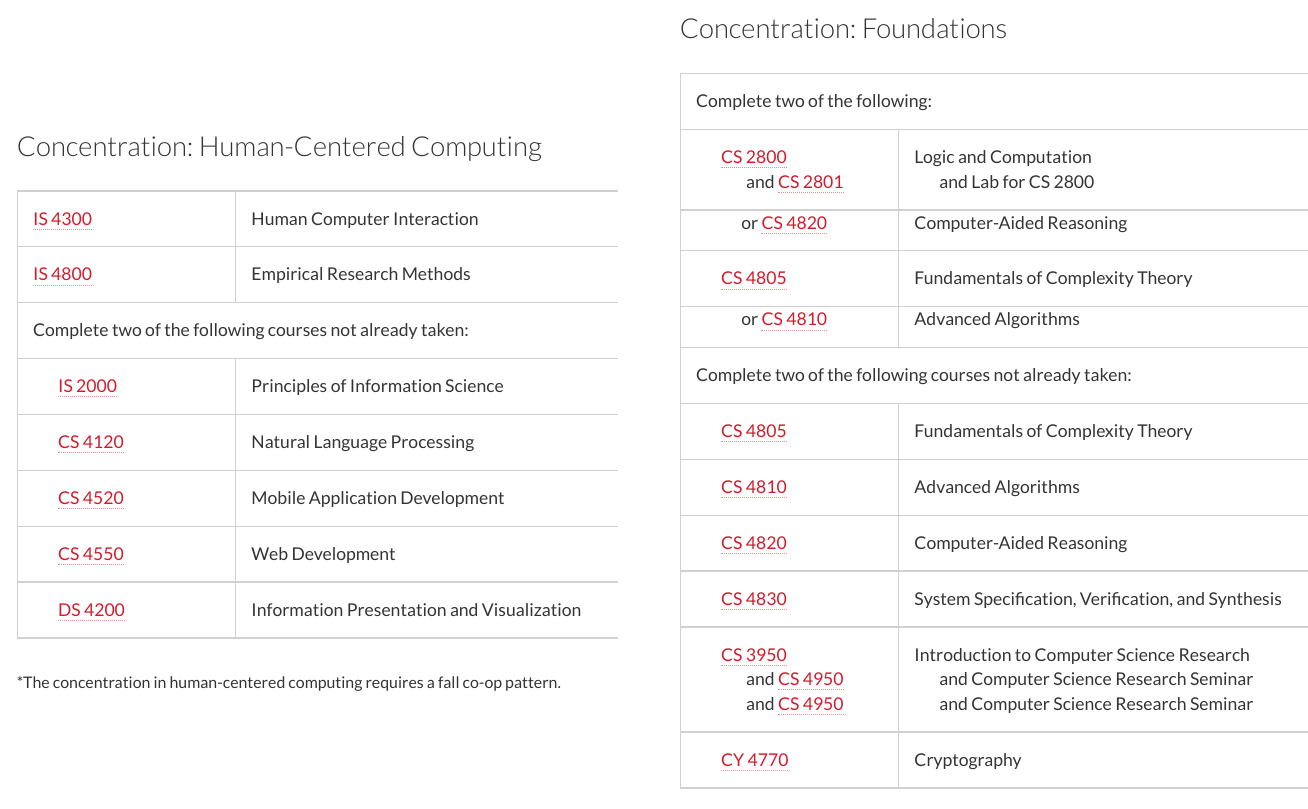

there are several concentrations a student can choose to do, including concentrations that are more theoretical and concentrations that are more industry focussed.

-

only one low level course required

-

a theory of computation course is required

-

there is also a statistics/mathematics course that is tailored for the computer science major: "Studies the methods and ideas in linear algebra, multivariable calculus, and statistics that are most relevant for the practicing computer scientist doing machine learning, modeling, or hypothesis testing with data"

-

students learn about Turing machines, Church-Turing thesis, automata as part of their version of CPSC 320. Students at UBC can also learn about the mentioned concepts but in another course (so it’s optional)

-

there is a strong theory base for computer science degrees, but after that your degree can be theoretical or industry/skills focussed

In Canada, computer science seems to be treated closer to science, meaning students don’t take many computer engineer-like courses. In the USA, computer science seems to be treated more as engineering, meaning students usually take a few low level hardware/systems courses that electrical and computer engineers take.

Each university’s core curriculum are pretty similar in regards to courses in operating systems, systems programming/computer systems/computer organization. I’m guessing this is because many universities will teach students about the Linux operating system. This is probably because Linux is open sourced so it’s easier for professors and students to access (they can access Linux through university servers), and how there’s basically only two operating systems Linux (Unix/MacOS) and Windows. Of course there are differences between Linux and MacOS, but the general categories of operating systems will be Unix and Windows. Additionally, since most systems programming has been done in C, 99% of the time C is the language of choice for these courses.

For data structure and algorithm courses: At UBC, C is used for CPSC 221. USC also uses C for CSCI 104L. At UofT, I can’t seem to find what CSC263H1 is taught in, so I will assume no programming language is used, thought I may be completely wrong on this. NU also doesn’t seem to use a programming language in their data structures and algorithms course. Other then that, the data structures and algorithms course is pretty similar in content between schools.

What differs the most are the introductory computer science courses, and they differ drastically. UBC[16] and NU’s[17] introductory computer science course follows the HtDP curriculum (that teaches a functional programming paradigm) using teaching languages like BSL. USC[18] uses C++ and teaches low-level concepts and imperative programming. UofT[19] follows the book "Practical Programming (3rd ed): An Introduction to Computer Science Using Python 3" using Python to teach a bit of OOP but not really anything about pointers or functional programming(?).

Additionally, some schools like UofT, USC and NU offer "pathways" which list suggested/required courses a student should take. For instance, there are specializations like "HCI", "Systems", "Foundations", etc. UBC doesn’t have something like this, but students could form their own pathway (it’s just not as explicit). These pathways allow students to choose if they want their degree to be more theory based or skills based.

The Different Types of Schools

There’s a school of thought that functions are either pointers or values. A C programmer would say "well functions are simply pointers in memory". A Racket or ML programmer would say "well we treat functions just like data, so they are values". What about the Java or Python programmer? Well, I’m not sure. An introductory computer science course usually falls within one (or neither) of these schools.

The TAs for the class I'm teaching, Principles of Imperative Computation, got me a "Functions are Pointers" jacket. (These jackets are in opposition to the "Functions are Values" jackets from the functional programming TAs.) I now wear it to point at functions. pic.twitter.com/godT7tPf2g

— ✨ Jean Yang ✨ (@jeanqasaur) April 26, 2018

I think the introductory computer science course, and higher year courses a university offers, greatly influence a student’s degree, and their perception of computer science. Based on how a university conducts their introductory computer science course and the upper year offerings, I’ve come up with three types of schools.

The Engineering (Pointer) School

Schools in the USA that classify computer science under engineering such as USC fall into this category. The computer science degree will be similar to the computer engineering degree in the first year, with students learning C++ and some hardware-focussed courses like embedded systems.

The Pointer school then uses C++ for majority of the computer science courses, including the introductory computer science course. This means students learn about pointers and memory management early on in their computer science degrees. Theoretical concepts are covered in later years of the degree.

Thus, the course is modeled around the programming language, rather than

the programming language being modeled around the concepts. As an

example, in the first computer science course at USC, students must

learn data representation of integers and strings before they can use

them in C; this is because C is a low-level language. Concepts are

more concrete rather than abstract, like learning about "passing

arrays". Someone learning functional programming doesn’t need to know

how integers and arrays are stored in memory or whether they should use

u16 or u32 in order to use an integer or array.

Engineering schools can also be industry schools because higher level courses will offer more industry skills and focus on teaching "fashionable programming languages and currently popular programming paradigms"[20].

The Functional Programming (Theory) School

Schools like UBC or NU fall into this category, and teach the

introductory computer science course based on a systematic approach

(Structure and Interpretation of Programs/HtDP, UBC and NU both using HtDP)[21] using an

educational programming language in the functional programming paradigm.

This systematic approach stresses "explicit and systematic approaches

to program

design"[22], rather than worrying about number representation, pointers

and memory management that pointer/engineering schools would focus on. A

functional programming paradigm is usually used because it’s easier to

reason about: no mutation, data and state are separate, and it looks

similar to algebra (given an input, you get an output). Thus, there is a large

emphasis on forming well designed and correct programs and using

concepts like recursion which can be easily proved correct through

induction. Whereas to prove a for loop is correct you require more

steps. Many more theoretical concepts are covered, due to the simple

nature of the high level educational language, which allows students to

focus more on learning and practicing abstract or theoretical concepts

like recursion and higher order functions. In general, there is a focus

on aligning programming with mathematics, for instance by the

"composition of functions and expressions"[20].

In regards to upper year offerings, NU has course offerings in Computer-Aided Reasoning, Complexity Theory, and System Specification, Verification, and Synthesis (to name a few). These types of courses are more of the "formal" and "mathematical" nature, and rarely offered to undergrads at other universities, including UBC! Even similar courses can differ at a theory school. At UBC, the compiler course is taught in Racket and centers around creating a compiler for a functional language, whereas at UofT, the compiler course is taught in Python and the project is a compiler that targets an imperative language.

A theory school provides you a stronger theory background, which is good if you will plan to go into grad school or research.

The Java or Python (Industry) School

I first learned about the concept when reading a paper[23] about using teaching languages to introduce objects and eventually OOP. While reading the references, I was intrigued by a blog post called "The Perils of JavaSchools"[24], which is where I learned the concept of a JavaSchool.

What is a JavaSchool, or more generally an "industry" school? An industry school is one that teaches what is currently popular in industry, aka "teaching fashionable programming languages and currently popular programming paradigms"[20]. For the introductory programming course, a popular mainstream programming language like Java or Python along with a popular programming paradigm, such as object orientated programming is taught. Concepts like pointers or recursion are merely brushed over, or never even mentioned until the systems course or the algorithms course.

You may be wondering if teaching object oriented programming (OOP) is a good weed-out substitute for pointers and recursion. The quick answer: no. Without debating OOP on the merits, it is just not hard enough to weed out mediocre programmers. OOP in school consists mostly of memorizing a bunch of vocabulary terms like “encapsulation" and "inheritance" and taking multiple-choice quizzicles on the difference between polymorphism and overloading. Not much harder than memorizing famous dates and names in a history class, OOP poses inadequate mental challenges to scare away first-year students. When you struggle with an OOP problem, your program still works, it’s just sort of hard to maintain. Allegedly. But when you struggle with pointers, your program produces the line Segmentation Fault and you have no idea what’s going on, until you stop and take a deep breath and really try to force your mind to work at two different levels of abstraction simultaneously.

The Perils of JavaSchools

I didn’t choose to attend UofT and UofC for computer science because they were industry schools that taught OOP using Python in the introductory computer science course, and many of their higher year courses didn’t seem interesting to me. But they may seem interesting to someone more industry orientated.

Another argument against teaching OOP in the introductory computer science course is that the "complexity of object-orientated programming bears little fruit"[20] for first year students.

It makes no sense to teach students how to engineer structure of large programs when they are yet to write any programs with a complexity worth structuring.

Why Computer Science Doesn’t Matter

Industry schools will also have upper year courses like "web development", "mobile development", or computer science courses that are also business oriented. USC, UofT and NU have courses like this.

With that being said, industry schools prepare you to with skills to write software for the industry.

Why make the distinction between "Pointer" and "Industry" School?

Computer engineering and computer science are frequently confused. Is the operating system more part of computer science or web development? Should computer science students learn how to interact with memory if they probably won’t be writing code that uses Linux system calls?

Computer engineering is more associated with how a computer works, down to the circuits and metal bits, in addition to assembly and C. Pointer schools which classify computer science as part of engineering likely have more low-level courses and an emphasis on low-level concepts.

On the other hand, an industry school sees computer science more for being software that has been created with high-level languages like Java. Thus, industry schools won’t focus on low-level concepts that much, because popular languages like Java, Python and JavaScript have abstracted away the details of memory.

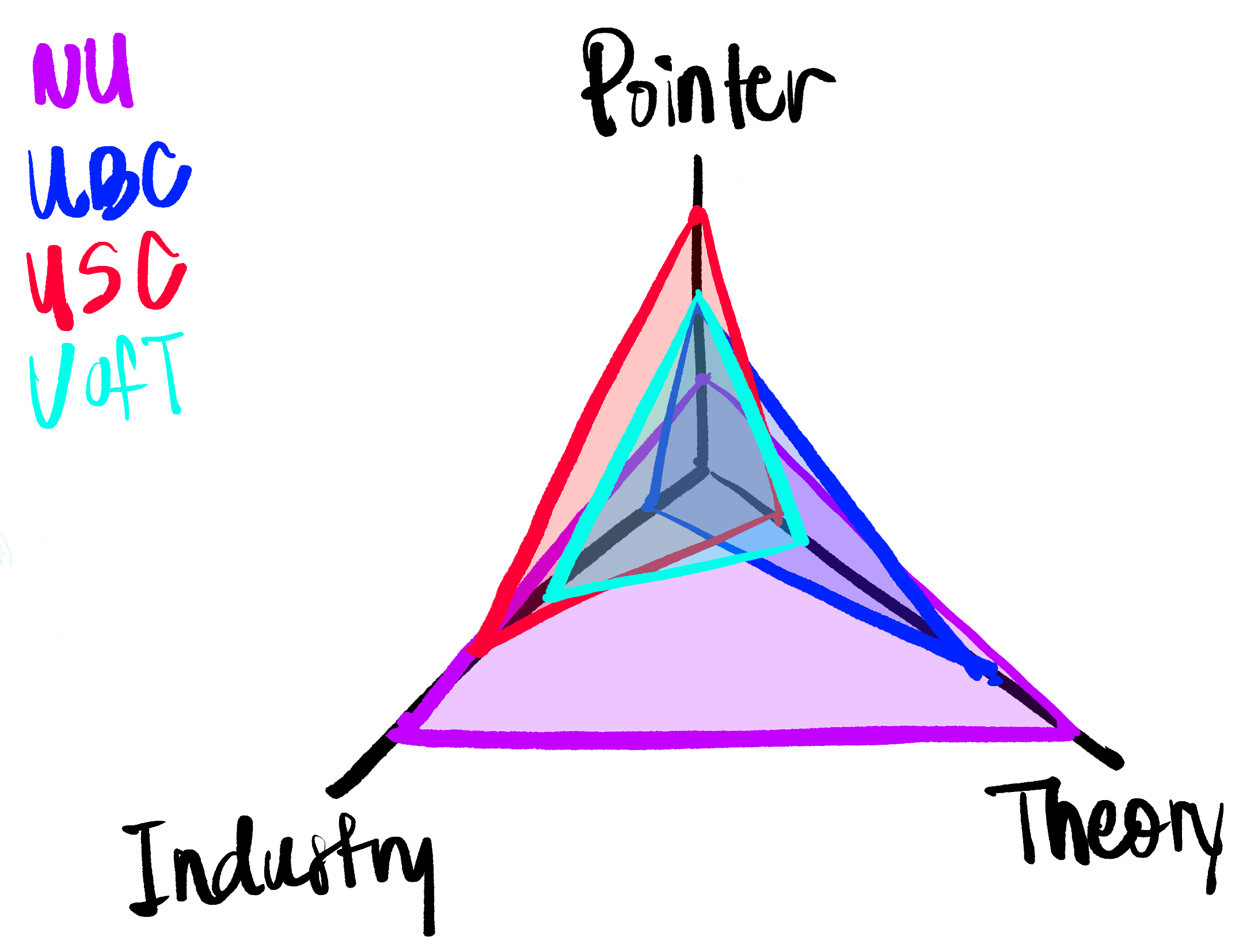

This is how I would categorise the four schools I analyzed

Are Computer Science Degrees too Theoretical?

T frequently hear people complain that computer science degrees are useless. This probably occurs more at UBC than other schools because there aren’t many courses that contain "industry skills" like web development. The only course that teaches web development technologies at UBC (CPSC 455)[25] is only offered in the summer. UBC has many higher level theory based courses, like Definition of Programming Languages (taught in Racket), Introduction to Compiler Construction (which is applied because there’s a project, but taught in (a functional paradigm) Racket, which students may feel is more "theoretical" than say using Python like UofT does), Numerical Linear Algebra, Computational Optimization and Advanced Algorithms Design and Analysis to name a few. Besides the web development course offer in the summer, there aren’t many courses that directly teach "popular and hot"* industry skills at UBC.

*There are game development courses at UBC, but most computer science students aren’t interested in game development due to the lower end salary and grueling hours as compared to a Big Tech job.

Meanwhile, at USC, NU, and UofT there are many more courses that directly teach industry skills. At USC, there are courses called "Programming Graphical User Interfaces" and "Android App Development". Similarly, UofT has "Programming on the Web", "Designing Systems for Real World Problems", "The Business of Software". At NU, students can choose to make their degree more industry focussed or theory focussed, hence why NU is strong in both theory and industry in the radar chart above.

In regards to the core computer science curriculum, NU’s is the most theory based. Students learn about the Turing thesis for instance, which none of the other 3 universities require. Next is UBC. UBC’s focus on a functional paradigm makes it more theory based than USC or UofT, which teach their introductory computer science course with an low-level / OOP focus, respectively. USC and UofT are close in terms of their core computer science curriculum, but UofT edges USC over theory based on computer science course offerings; UofT has more theory based higher level course offerings than USC. This is just my observation.

Maybe you’re wondering why there’s so many differences in how universities teach computer science. Different schools can really offer a different computer science education to their students. Well I think it’s because of the confusion of what computer science is.

there is a widespread belief that computing science as such has been all but completed and that, consequently, computing has "matured" from a theoretical topic for the scientists to a practical issue for the engineers, the managers and the entrepreneurs, i.e. mostly people —and there are many of those!— who can accept the application of science for the obvious benefits, but feel rather uncomfortable with its creation because they don’t understand what the doing of research, with its intangible goals and its uncertain rewards, entails.

The end of Computing Science

The question we need to ask then:

Is the computer science degree for students who wish to pursue research in computer science to think of correct and novel ideas, or for the student who only cares about being correct and working in the software industry?

Currently, the computer science degree at many schools tries to do it all: prepare students for grad school and prepare students to create web applications in the software industry.

I don’t think this is good because one area severely lacking in many computer science degrees (not in the curriculum or offered in higher level courses) is reasoning and formal verification of systems and type theory, among other areas of theoretical science. Dijkstra also thought the same many years ago!

Until the end of his life, Dijkstra maintained that the central challenges of computing hadn’t been met to his satisfaction, due to an insufficient emphasis on program correctness (though not obviating other requirements, such as maintainability and efficiency)

I don’t think universities are equipping computer science students to do research in areas like formal verification, dependent types, compiler correctness and more. I also don’t think computer science degrees are equipping students well for the industry either. There needs to be a different path for computer scientists and software developers, like there is for chemists and chemical engineers. Computer science is a different subject than software development[26].

The question is then is the computer science degree too theoretical? If the computer science degree is to prepare students to do research where they must think of correct and novel ideas in the field of computer science, then no, the computer science degree is not too theoretical. It actually isn’t theoretical enough.

Of course, this means there should be a different degree for people who want to work in the software industry, with coursework that is more user focussed and practical[27], rather than theoretical. The issue is that there’s no clear definition of the "Software Engineer" discipline like there is for chemical engineering, so Computer Science is treated as a giant umbrella term. While there are overlaps between the two fields, I believe they are distinct enough to warrant a split.

For instance, we can all agree that software is laden with bugs and as Dijkstra says:

On the contrary, most of our systems are much more complicated than can be considered healthy, and are too messy and chaotic to be used in comfort and confidence. The average customer of the computing industry has been served so poorly that he expects his system to crash all the time, and we witness a massive worldwide distribution of bug-ridden software for which we should be deeply ashamed.

The end of Computing Science

Verifying programs is hard. But everything is a program in computer science! A compiler is a program that takes in a program and outputs another program! It’s one thing to write a program, and another thing to verify a program is both useful and correct.

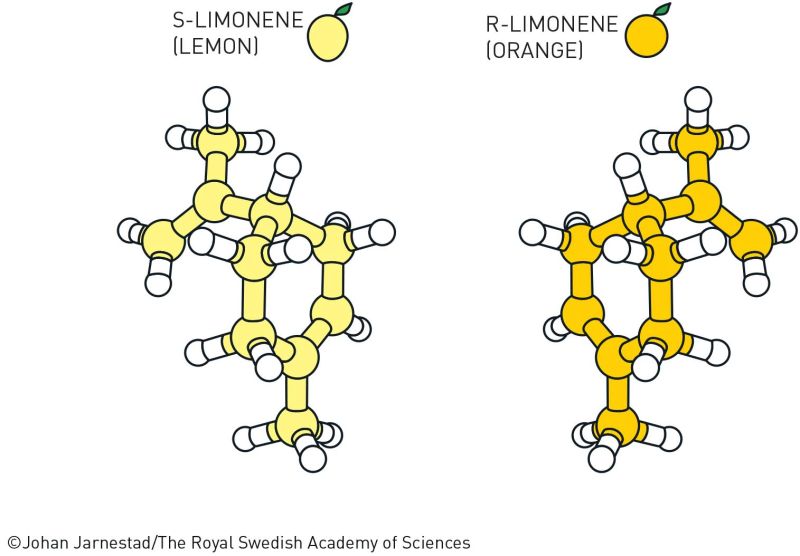

I liken it to the production of drugs. It’s one thing to discover a drug, and it’s another thing to synthesize that drug. Then it’s another thing to learn how to synthesize that drug on a large scale as safely and effectively as possible. Without someone who understands the theory, you can’t think of a way of making a drug. For instance, an novice chemistry student may find the formula to create a drug, and realise they have unfortunately created stereoisomers of the drug. But only one stereoisomer of the drug works; in most cases, the other stereoisomers are not effective or even harmful. While there are ways to filter the products, but this means you waste around half of your products, which is not good because many drug precursors are byproducts of the oil and gas industry[28], so we don’t have an infinite supply. This is a hard problem in chemistry, the solution being awarded a 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry[29].

For a long time, drug makers were stuck having to filter out their products for the correct stereoisomer. After years of research, there are now ways to conduct "asymmetric organocatalysis", meaning you only create one stereoisomer. Similarly to program verification, we are currently stuck writing tests. But "testing cannot prove the absence of bugs it can prove their existence"[30]. For now, we are just stuck writing tests among tests and hoping for the best, like the novice chemistry student was stuck just filtering out the products for the correct stereoisomer.

How can the ability to easily verify a program is correct be achieved? How do we prove the absence of bugs so we don’t get catastrophic scenarios like NASA[31] sometimes does? With research. Which requires a strong understanding of theory. Right now, formal verification is an "unmastered complexity". Many problems in computer science are an "unmastered complexity".

You see, while we all know that unmastered complexity is at the root of the misery, we do not know what degree of simplicity can be obtained, nor to what extent the intrinsic complexity of the whole design has to show up in the interfaces. We simply do not know yet the limits of disentanglement. We do not know yet whether intrinsic intricacy can be distinguished from accidental intricacy. We do not know yet whether trade-offs will be possible. We do not know yet whether we can invent for intricacy a meaningful concept about which we can prove theorems that help. To put it bluntly, we simply do not know yet what we should be talking about, but that should not worry us, for it just illustrates what was meant by "intangible goals and uncertain rewards".

So how do we figure out the "limits of disentanglement" and "trade-offs"? By equipping students with the theory required to think of correct and novel ideas.