I felt a sense of eagerness I hadn’t in a long time when the new school year started. It was like a fog was lifted in my 5th year of undergrad when I transferred into the chemistry and computer science combined major. As a fifth-year student, I thought I had honed in on the craft of being a university student. I had taken countless courses in different subjects and different year levels. I thought I was decent at juggling multiple courses and responsibilities. I thought that this year was going to be my year.

But that fog slowly set in again, and I made decision after decision that went against my gut instinct and ultimately harmed my mental and physical health. I was scared of rejection if I didn’t please others, and I continually made decisions that didn’t prioritize my wellbeing. And when the mornings started to become as dark as the nights, all I could feel was rage at myself for thinking too slowly, reacting the wrong way, or misinterpreting events around me. I was mad at myself for being human, which ironically was a very human thing to do.

When I started taking computer science courses, I gave myself the grace to "mess up" because I didn’t know anything about computer science. I permitted myself to learn and I had a growth mindset towards computer science. But I didn’t give myself that same grace for chemistry, because I was supposed to be good at chemistry. In junior high and high school I used my grades in chemistry as evidence that I was inherently good at chemistry, so I approached chemistry courses with the mindset that I was just "good at it". My teachers had parroted that idea to me for years, whether that was in good faith (not really) or because of the model minority myth, who knows? So at the young age of 13, I decided I was going to become a scientist who did chemistry. However, that image of myself I had dreamt of and plastered on a wall inside my mind when I was 13 years old was crumbling day by day. And I didn’t know how to deal with it. I approached my chemistry courses with the mindset that the concepts would quickly and easily make sense to me. And when my statistical thermodynamics course started to sound like a cacophony instead of a symphony, I panicked. Whenever I got lost in reviewing a concept I felt too nervous and anxious to continue learning, so I stopped. Gregor from CPSC 110 always said a headache meant you were learning! But when I was studying my third and fourth year chemistry courses, I panicked when my head started throbbing, because I had never felt that way in high school (or first and second-year chemistry courses).

When I was in elementary school, I became friends with my neighbors, who had a backyard with a hot tub and swing. And because I had a trampoline, we would frequently play in each other’s backyards. That brother and sister duo became my first real friends. One day, when they asked me to come outside and play, my parents told them I was busy doing schoolwork. When my friends packed up and moved away, I didn’t bother becoming friends with the new neighbors, because I was busy doing math workbooks. That was how a lot of my time looked like until high school; doing workbooks in math and science while the other children went outside to play. As a result, school was easy because I had already seen everything the teacher was teaching, not because I truly knew how to learn. I think my parents were doing the process of learning for me, allowing me to see the content multiple times explained in different ways. In high school, I would study until I collapsed and achieve high grades that way. In fact, for every exam, I’d study until I couldn’t open my eyes and write exams while being on 6 hours of sleep. I’d do this for every subject, especially chemistry. Now, I’ve realized that I wasn’t inherently good at chemistry. I had either already learned the material, or I was young and healthy enough to brute-force memorize everything for hours on end in a high school.

learning is hard

With that being said, not only was I not properly learning, I was also too scared to face the fact that I didn’t know or understand my courses. In my quantum chemistry course and my statistical thermodynamics course I found myself feeling lost for as long as 3 lectures in a row, which was when the panic was enough to turn into fear, which finally forced me to sit down and try to learn the content. That fear is something I’m learning to untangle from things I want to learn about. The fear of failure, the fear that I’m a failure for not understanding something the moment I read it, the fear of "falling behind" as I review a concept for the 10th time. I was scared of learning about things important or fascinating to me because what if I couldn’t understand the Boltzmann distribution? Then how would I understand the Boltzmann equation? Then how could I understand entropy? I fell into these pits of doom, planting more and more things I "didn’t know" how to do because I didn’t understand a concept. With fear as a driving force to propel my learning, I yearned to do things that could feed my self-esteem and make me forget about the content I needed to learn; things that were "easy" to do. I’ve now learned this behavior (working on a task that is easier and less important) is called the bike shedding effect.

effective leadership is hard; being passionate is not enough

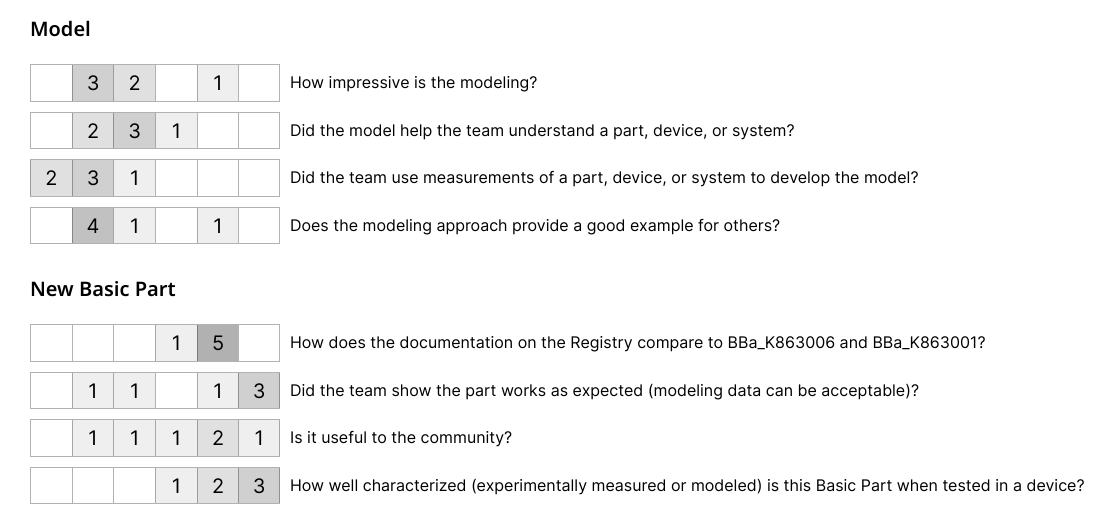

That easy task was working on the UBC iGEM Wiki. During my first week of midterms, I spent more time working on the iGEM wiki than studying for 3 midterms, and I paid the price by performing horribly on my midterms. I did so horribly that I had one of many breakdowns that led me to rethink my priorities, time management skills, and who I trusted. Seeing bad grades caused a huge dip in my self-esteem, and rage that I didn’t know who to direct towards, besides myself. My boyfriend asked me, "Why did you spend so much time on the Wiki?". Besides not wanting to study, I wanted to do something useful, because I was the only member on the iGEM team that was adept enough in programming to implement the wiki. So I thought I was giving my time and energy to a team well prepped to compete at the Global Jamboree. And because iGEM leadership had given me no indication of the actual situation occurring within our team, and since I had been in other clubs with transparent leadership, I never doubted what they told me (or the lack of what they told me).

iGEM consists of three subteams, dry lab, wet lab and human practices. I was apart of dry lab, ad our subteam was working very well with each other (except for one individual). While I knew what was happening in my own subteam, each subteam was quite isolated from the other. This resulted in general meetings that were useful to no one, because no one understood what was happening outside their own subteam. Unbeknownst to me, but known to the co-directors, was that over half the wet lab team was no longer responding to leadership, with 2/3 leads having ghosted the team and no replacement for those leads. Our experiments were also not being run because an important piece had been lost and no one was stepping up to rectify the issue. iGEM leadership was not transparent to the remaining members of the team with how poorly the most critical part of our project was panning out. With blind faith, this led me to over-commit my time, alongside some other members who are still recovering from the events that transpired. I believe the co-directors were not transparent with me on the progress of the project because they feared that I would not have given my time and energy to develop the wiki (which was an easy but time-consuming task). And that was a large breach of my trust towards them, as a subteam member and as a friend. (These events occurred with co-directors during the 2022-23 season).

Our wet lab performed so horribly that the other subteams efforts were in vain. Without a proper wet lab component, our co-directors added further salt to the wound by getting angry at those wet lab members who left, instead of analyzing what went wrong with the remaining members on the team. That had also rubbed me in the wrong way, because I was so used to doing reflections in my software and research positions that I couldn’t believe that the co-directors weren’t discussing with the team what went wrong besides "fuck wet lab". Our dry lab members, who had done well, didn’t even get any acknowledgement from the co-directors. Similarly so for human practices.

Should I have spent so much time on a task that was trivial and antithetical to my goals (of doing well on midterms?). No, and I take fault for that. But should I have spent any time on a group project that was halfway to the grave? Of course not, and I was blindsided in that regard, alongside some other members. When I could finally analyze the situation that had occurred, I was so appalled at how the co-directors had handled these events. From my point of view, these are the causes of our team dysfunction and lack of transparency:

-

Expansion of our team: The 2022-23 team expanded from around 10-15 members to a team of 20-25 members. No processes or policies were set to facilitate this transition. When teams become larger, it becomes harder and harder to coordinate a project. If there are no policies indicating how information is to be communicated or documented, information will usually stay between a small group of people, leaving others with no clue as to what is going on. Lots of members would store their research and notes on their private computers, or send important tasks and papers through private slack DMs. When someone was confused about a concept, they didn’t know where to go or who to ask. Because our team is large again this year, I created an internal documentation system. When I expressed the lack of processes to facilitate a large team (with many new members) to the previous co-directors, they dismissed me and said that they didn’t actually expect to have a team of 25 people, but to have people drop out and be left with around 10 members. Both previous co-directors worked with the idea in mind that "It’s better if I do it myself." and that people who actually "cared" about the project would stay and work on it. This meant the co-directors were unlikely to help a new member do something if they could do it faster. I feel that as a leader, this is an inappropriate to treat a new member. This leads to my second point.

-

Treating new members as dispensable: The 2022-23 co-directors treated many members as "dispensable", especially new members in wet lab. When the wet lab leads were neglecting their tasks such as attending wet lab meetings and training new members, they weren’t reprimanded. Instead, the co-directors assumed the task of leading wet lab and training new members, unbeknownst to other subteam members. With absent leadership in wet lab and human practices, the co-directors decided to start leading these subteams (until a new member stepped up to lead human practices) which took away from their ability to properly lead the whole team and ensure the success of the project. Because leadership become hostile and unstable, and returning members who were leads could get away with neglecting their responsibilities, many new members did not understand what their place on the team was and didn’t feel like they could learn in this environment. Because new members were treated as dispensable, many left. When I argued that we should aim to retain team members through actively teaching them and encouraging them to stay, the prevoius co-directors said that the effort wasn’t worth it, and that people who actually cared about the project would stay. However, this goes against our motto that anyone can join UBC iGEM, even those without experience. The remaining members that stayed were all people with prior experience. All members who were hired without experience ended up leaving. When a club makes a promise that they welcome students of all experience levels, older and more experienced members must step up to make these new members feel valued and teach the the skills to eventually turn these new members into individual contributors.

-

Picking a project that was too complex for a new team: Our project was hand designed by the two wet lab leads who left the team. But before they even left, there was no effort to help the rest of the team understand the complex mechanisms of the project. Everyone was expected to learn about the project themselves, or try to read through messy notes created by the wet lab leads. As a result, no one had a clear understanding of the project and team morale suffered. When half the wet lab team left, there was no one outside of wet lab who could rectify the solution besides the two wet lab leads that left. With the environment of the club becoming increasingly hostile, this made asking questions about the project harder too.

I think the 2022-23 co-directors were passionate about science, but they didn’t believe in our team and did not value new members because they couldn’t create results from the get-go. With that being said, I became a lot more vocal with our new co-directors about my concerns. I also started implementing the ideas and processes that open source communities and software companies used, such as a documentation system via mdBook, created by the Rust Foundation to document software packages and utilities. As a new dry lab co-lead and wiki lead, I am pushing for many open source and software practices and processes into our team, including documentation practices, making your work open and more.

After my first set of midterms, I did better on my second set of midterms, but I knew the way I was spending my time reviewing was not optimal. For computer science courses, I actively reviewed my lectures, redoing problems and solving practice questions vs. passively staring at slides. But in high school, I had passively studied for all my courses with success, so I applied that to my chemistry courses; this yielded horrible results. Looking back now, it’s hard to understand why I would actively review for computer science but not for chemistry. However, I was doing what felt familiar and safe to me, because passive studying (reading slides or rewriting notes) doesn’t push you out of your comfort zone. It doesn’t challenge your ability to apply concepts. Passively reviewing didn’t cause me to panic, but I wasn’t learning anything. When I started studying for finals, I finally decided that I needed to face the fear and panic I felt when I didn’t understand a concept. I collected all the practice questions I could find and did all of them. Sometimes I’d only do 3 questions in an hour. Sometimes I only did one. Only when I exhausted all practice questions did I allow myself to go back to passively reviewing. While I was doing practice questions I felt moments of panic but I kept pushing through because I knew logically doing questions was rigorously testing my ability to apply concepts, which passive studying could not do.

staying healthy is hard

This year has taught me many hard things. With my mental health sliding lower and lower, it became harder to remember to practice physical health. Because working out was a mental break for me, I became obsessed with more explosive and heavyweight-focused workouts, leaving me out of breath but also stiff and sore the days after. I had to resort to physiotherapy because my back became so stiff it was painful to bend over and sit down. Recently, I have tried incorporating more stretching and pilates into my workouts, which emphasizes a more controlled and structured way of moving your body. I’ve exercised since I was 13, with a single goal of burning as many calories as possible, but recently I’ve decided to exercise to become strong, agile, and flexible.

Well that’s all for now! I hope this wasn’t too boring and I’ll go back to eating some chocolate now.